Glossary of Music Compositional Terms

Glossary of Music Compositional Terms

Glossary of Musical Terms

I am looking for the edge of what you can hear. I can just about hear it but I can’t quite. That’s the thing I want. How do you get there? It’s a travel because it’s way on the horizon. And sometimes you find it to make something that has magic. – Paul Simon on the Late Show with Stephen Colbert

It was brave of Charles Wuorienen to write Simple Compositon. There, he layed bare things he cares about. Gradually, the reader can start to discern the outlines of the shadow, of all that Wuorinen did not have on his radar. That’s my hope for this. This is how a circle of composers talked about these terms and the shadow will emerge, the overweighting and underweighting, etc.

We learn by doing together. None of the doers I fell in with thinks in precisely the same way. I will try to point out the range of takings surrounding various terms.

1918

I studied composition for a while with Joel Suben. He was the first to inculcate a sympathy for the bridge-burning. After the first great war and the next great war it was widely felt the old order had changed and in response music must make a clean break from the old ways. Schoenberg was at the heart of bridge burning after WWI, Boulez continued after WWII; with Leibowitz, Boulez issued a Diktat – everything has be 12-tones with equal weight.

The diktat set modernist mission creep into motion. Not all composers have it in them to compose like that. The vehemence of the diktat forced composers to work against their better natures. “Equal weight” – Schoenberg & Babbitt did not sign on. Don’t they weight and unweight, float and land? Such weighting and landing are the traditional doings that annoyed Boulez in the work of Schoenberg. Boulez wanted to burn the bridge still further, while Schoneberg, after his free atonal work, was ready to move on and saw a way to create something more orderly, his new classical style. Babbitt called himself a Schoenbergian, and Babbitt does traditional things in his own bizarre way. It’s to Babbitt’s credit that he acknowledges his debt to Schoenberg’s combinatoriality, but he did everything in his own very idiosyncratic way.

Bridge burning created a hard line at 1918, and the Rockwell Coup softened that line, with the help of composers like David Del Tredici, whose music sometimes dares to bring back pre-1918 functional harmony.

The Rockwell Coup encourages us to look beyond Schoenberg to Schoenberg’s guiding light, Brahms. Brahms is now closer to the center of the family.

The Family

We are not fossils yet. We are in motion. We are moving targets and what we seek is also moving. By the time we get what we seek, it may be useless.

I fell in with some composers and I am trying to document how we spoke about these terms as ways forward, with the aim of disovering and exploring how things work and levering ourselves out of ruts and finding The Road to the Open – Der Weg Ins Freie. (Arthur Schnitzler)

More specifically, I am interested in maximalists getting real and minimalists growing rich in complexities.

An example of the former is Babbitt’s overcoming the taboo against diatonic harmonies in his “Swan Song No. 1”.

An example of the latter is the wonderful and unforgettable harmony that over-foregrounds (see Over-foregrounding) toward the end of Julia Wolfe’s work about John Henry. I wrote about it somewhere. Another example of the latter is the clearly delineated interval content in each number withing David Lang’s “Little Match Girl”. Each seciton has the profile and harmonic integrity – low entropy – comparable to each section of Harold Meltzer’s “Brion”.

William James is a role model. He shows us how to enlarge our family as much as is humanly possible. Jacques Barzun likes to point out that James held long conversations with people who held vastly different beliefs. He defended and promoted many of those. Others have pointed out that James does have one prejudice that he left unchecked. See his dsicussion of Catholicism in The Varieties of Religious Experiences. James pushes back against logical positivism in various ways and there is an “unreconstituted logical positivist” lurking here – Milton Babbitt.

Ben Boretz is another role model. He is for Open Space. He also pushed back against Milton Babbitt, very early on, and Babbitt heeded. I think this is not very well known.

What values are shared widely? What brings us all together? What framing of this family creates the largest family?

With few exceptions (David Del Tredici), composers are not doing funtional harmony. It’s fun to see pop music slowly drifting away from functional harmony, often through slippery Villa-Lobos moves on the guitar –

The Rockwell Coup

David Amram’s version

David Amram & I both knew Gunther Schuller. Schuller was Amram’s French horn teacher at Manhattan School. I knew Schuller form my years at Tanglewood in the 80s. Gunther sat in on rehearsals of Jemnitz Triosonate for guitar, violin, & viola. Louis Krasner coached. Gunther conducted Louis Andriessen’s De Staat at Tanglewood. John Dirac was the other guitarist. A few years later Gunther conducted the NY Philharmonic’s De Staat on the Horizons Festival. David Starobin played the other guitar part and Scott Kuney played bass. The brass players were super obnoxious. They didn’t like guitars in the orchstra and the hazed Gunther mercilessly. Andriessen was so hopeful after the first rehearsal. It came together so quickly, but it got worse in each successive rehearsal and he was disappointed with the performance. I last saw Gunther at The Stone in 2014(?). He was there to hear the solo guitar piece by his student Mohammed Fairouz.

Rockwell convinced Paul Fromm that there must be an all-Glass concert at Tanglewood.

Fromm took the request to Gunther Schuller, who explained that he is happy to program Glass, but he never does programs featuring a single composer. So Fromm fires Schuller. I guess it wasn’t a request after all.

Leon Fleisher’s verion

I was at Curtis with Bridge Records records for the recording of Leon Fleisher’s album, All the Things You Are. Included on that CD is George Pearle’s set of pieces. The set is dedicated to Leon Fleisher. Each movement is dedicated to someone who was fired from Tanglewood, including Richard Ortner.

Richard Ortner was the one who called me every summer throughout the 80s with the great news that I was needed for guitar parts at Tanglewood. I was sometimes working at our family friend’s hobby farm, an equine spa for race horses. I was mucking out stalls. A high point was driving the tractor with its trailor full of muck. The call from Richard Ortner commuted my sentence at the equine spa.

After getting fired, Fleisher asked Ozawa for some feedback, asking, “What was missing?”

Ozawa: “tabasco sauce”

Is the missing “tabasco sauce” clarity and practicality? When I talk about the hot mess of modernist mission creep, I’m talking about a lack of clarity and practicality. The Rockwell Coup is certainly an over-correction. That’s the way corrections work. Put a pin in the plethora of exciting new modalities that emerged in the 20th C. I call it the “Burgess Shale” of compositonal techniques. Put a pin in that because we’ll pick up where we left off. We’ll return with greater clarity, practicality and humility.

The Burgess Shale provides crucial evidence for the “Cambrian Explosion,” a period of rapid animal diversification, revealing many unique, soft-bodied organisms with body plans unlike modern animals, suggesting an early proliferation of diverse phyla that were largely evolutionary experiments, many later extinct, challenging simplistic evolutionary narratives and highlighting the contingency of life’s path. While initially seen as entirely new phyla, modern cladistics suggests many were stem groups or relatives of existing phyla, though the sheer morphological disparity remains a key feature, showing an early, less-constrained evolutionary experimentation before competition narrowed options.

Holding

–We can hold a rhythmic motive that may be dressed in diverse harmonic things.

–We can hold a harmonic thing that may proliferate in various rhythmic profiles.

–The ideal of binary form and sonata form is of a tune/harmony, where the tune brings with it a rhythmic profile.

What we want to avoid is erratic or capricious setting and erasing. Hold something for a sustainable duration to set up a dramatic break. We hold to make a break. Breaks are expressive ends.

What is held, in the following example, we call a “focal collection”. It doesn’t have to behave like the triad that is prolonged in the Schenker universe, but we think focal collections can behave that way. There’s debate about that.

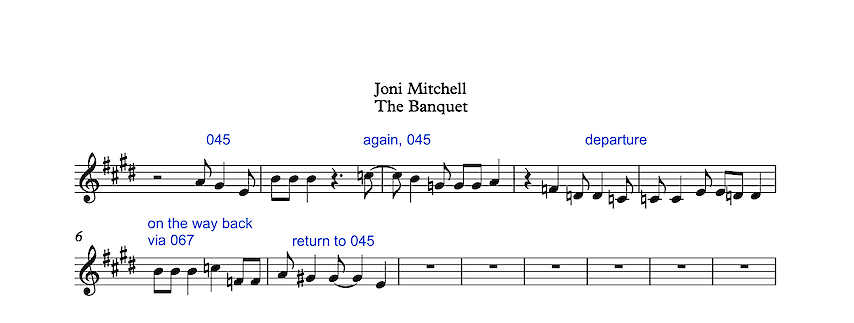

Here, Joni Mitchell tells a story about 045.

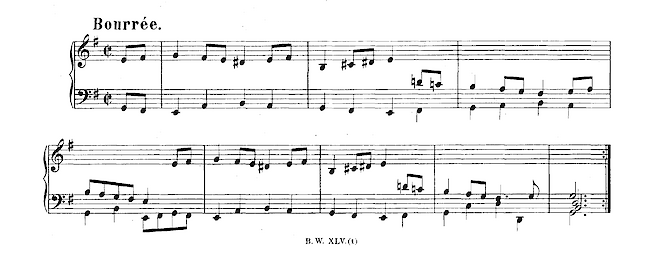

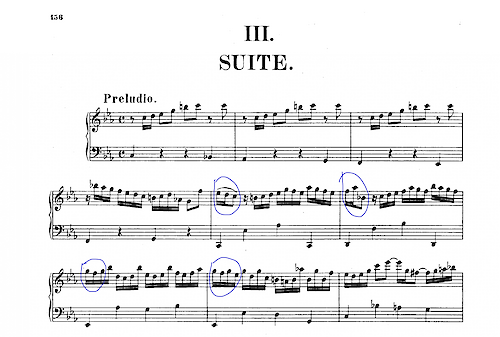

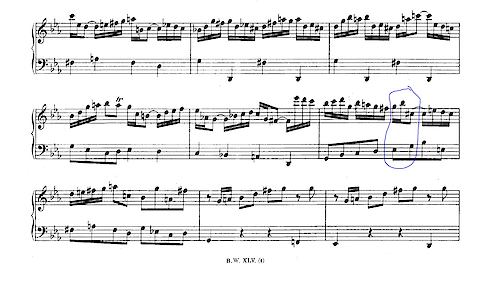

Here in BWV996 Bach has a longer story going. The suite deals with the relative major rising to supplant the dominant minor for its structural position at the end of the A section. It only achieves that position in the famous Bouree, wherein Bach tells us, in so many notes, that the relationship is an inversional one –

In bar 6 –

B - C# D# E - Dnat Cnat | B

looks like an imperfect palindrome, but it’s also a perfect retrograde inversion –

+2, +2, +1; -1, -2, -2

Bach is basically telling us that the relationship is nothing less spectacular than a pasage through a mirror. He was responding to the facile conventionality that the relative major had become among his galant colleagues. That’s my reading of Bach’s mind.

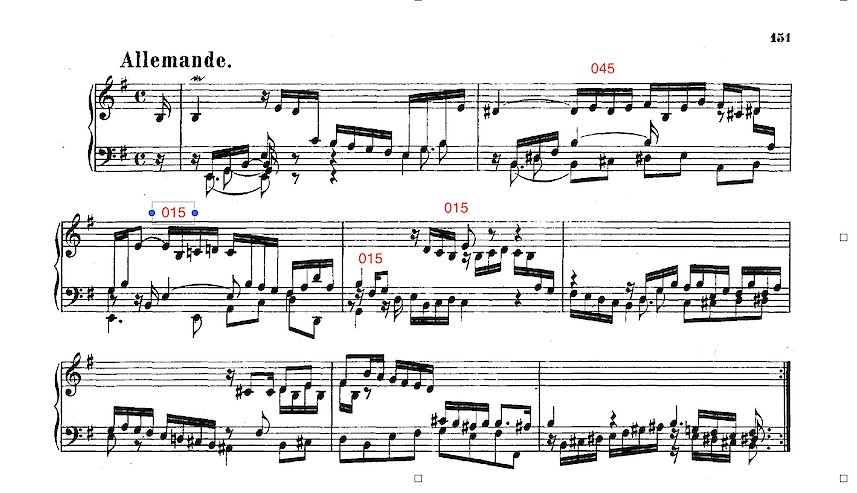

In the Allemande his move to the relative major is painted in 015 colors that he *holds* long enough to convince us that he’s holding that color. Reminds us of Brahms’ cello sonata – E - G - B C - B - etc.

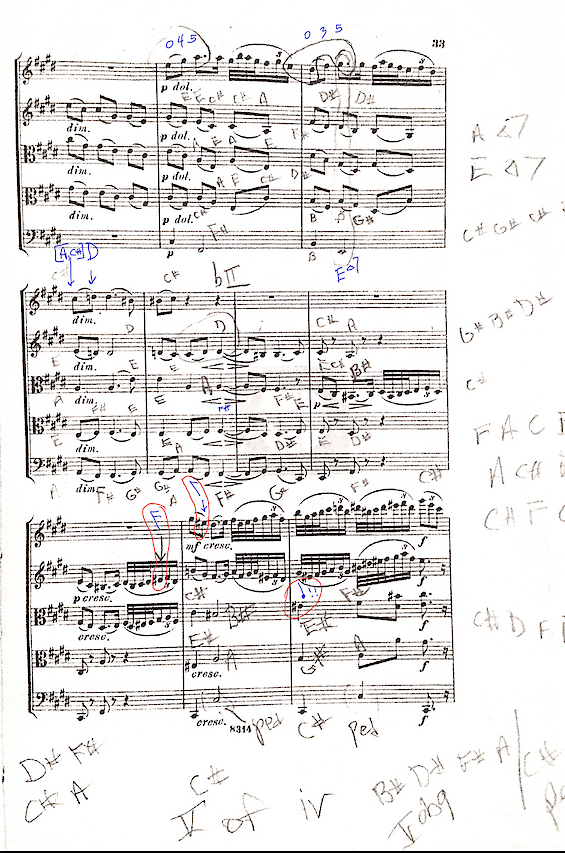

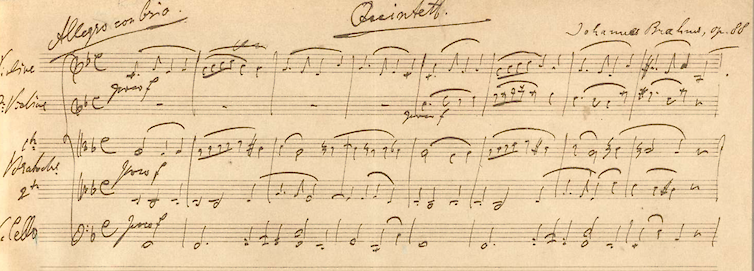

045 C - - F E - F - opens Brahms op. 88 and it has a future in the sarabande. Brahms carried his sarabande around with him in a notebook for yeears and years, and eventually he found its reason to be in op. 88.

The structural keys of op. 88 are b6ths of each other – F, Db, A. However, the dominants of each bear structural weight as well. The result is an augmented scale. F C; Bb Ab; A E – or 014589 – C Db E F Ab Anat

As Db becomes structural F, its dominant C and Db make an 015.

Schoenberg was fascinated by the augmented scale and the Princeton people found it very rich. They called it the E Hexachord.

014 – [C, F, E] as a thing, as a chord/tune, has a future in this saraband, but also in the structural keys – F C Db.

Horizontal and vertical 015s and 045s, but the bII chord makes puts extra weight on the D natural.

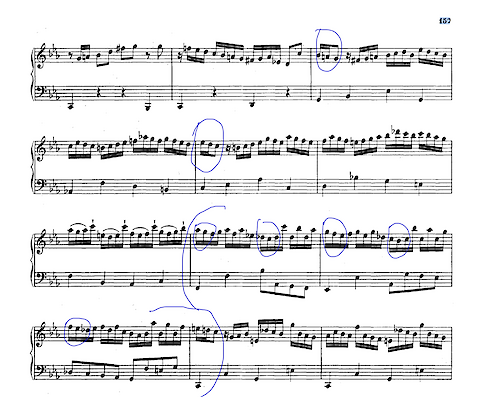

Next, and not unrelated – E# starts appearing in ever longer rhythmic durations, circled in red, below.

This reminds me very much of the moment when Wilhelm Meister first meets his love, his Amazon, after being punched out by bandits. She ministers to his wounds and his first impression of her, his destiny, is in a fog.

So this reaquaintance with F, in alien guise – E#. The opening bar is all there in strange colors: E – B# – E#, relating them to C#.

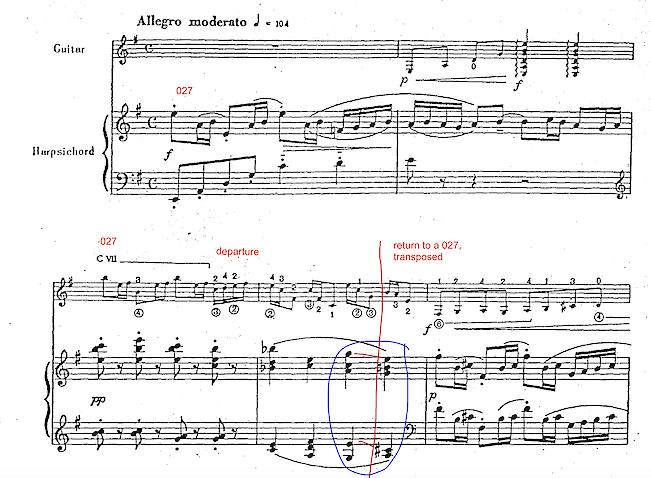

Here, in Manuel Ponce’s sonata for guitar and harpsichord, I think of 027 as being prolonged in much the same way that Schenker speaks of prolonging triads, but there’s not agreement about the words and and way to think about *prolonging dissonances*. We’re fighting the strict Schenkerians a bit on this point.

The C natural displaces the B and in bar 4 whole tone harmonies displace the 027 flavor. Departing strengthens the sense of return on beat 4 of bar 4.

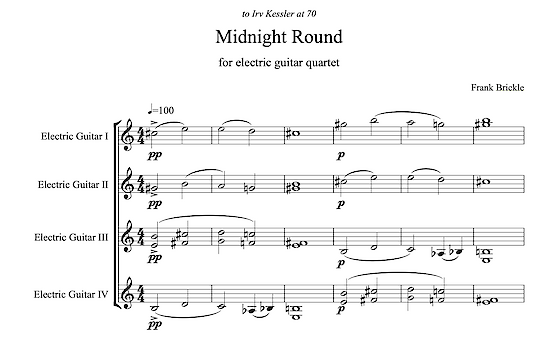

Frank Brickle liked a smooth mid-phrase, where the mid-phrase doesn’t depart from the focal collection, like a Webernian aggregate, or like a passage of tonal music that never departs from the triad.

Babbitt, to hold a sound, a chord (he’d say “a set class”), would gut his array and go Webernian for a spell. Brickle cited a viola & piano duo as an example.

In this example, Brickle is holding 5 consecutive members of the 5 cycle – [G# C# F# B E]. His phrases always begin and end on [G# C# F# B E].

This collection *is extended* by three intervening chrods before the 0 collection returns, re-disposed in bar 3.

1– [G# C# F# B E] is the 0 harmony

2–The second chord offers a lovely bump. [C# F# B E] is expected; the D natural kicks some dust in our eyes.

3–The 3rd chord is identical to the first –

4–The 4th chord – over Eb would be identical to the 2nd chord, but over Ab a new interval is introduced, the tritone. This is a harder, bigger bump than the 2nd chord. Moving Ab to Bb resolves the chord into a transposition of the 0 collection .

There are no Ebs, no D#s in the piece. These same pitches, shuffled a bit left or right, make the entire little piece. It’s all made of an 11-note aggregate.

We must grapple with terms. There is disagreement with the strict Schenerians and I need to discuss these terms with the Schenker people. Frank Brickle and Emil Awad support my contention that we can and we are prolonging things other than triads. We disagree with the Schenkerians who say we’re not allowed to prolong dissonances.

Babbitt didn’t press the matter. Joseph Strauss likes to say a hexachord *governs* a section in a work by Babbitt or Shoenberg. Brickle, Awad, and I like to say Babbitt is *prolonging* that hexachord.

When I first wrote about Swan Song, I mentioned to Babbitt that he lands some creatures that don’t want to be landed. Swan Song No. 1 is an all-trichord piece. When he lands 016 he does not try to subdue it. It’s like a very energetic fish on your hook, writhing around. Babbitt never responded to such comments. He would just nod.

But on some level, his treatment of every trichord is even handed. Some sit and others are eager to wriggle out of your grasp. But he lands them all.

Erasing

Stop holding whatever you’re holding – erase it.

Big moments are often erasures. Erasing isn’t bad if the surface is geared toward those big moments.

The erasure is a displacement, an opportunity for a watershed moment. If erasures are handled capriciously the result is hit or miss, scattershot.

Brickle got the cudgel from JK Randall. Brickle Claudio’d me with it. I needed to learn what he was talking about and after a long time, it sank in.

Too much erasing!

Liquidation

What’s the difference between liquidation and erasing?

Brickle: Liquidation is when, in a sonata, for example, the motives all boil down into very basic elements and whirl around in a bluster of scales and arpeggios.

I am beholden to the notion that what happens in one dimension can be enhanced by a complementary happening in another dimension. Can rhythmic liquidation happen independent of pitch liquidation?

Brickle complained about Sibelius. He said his material is liquidated from the outset. If that’s true of Sibelius, then what can be said about “Electric Counterpoint”?

Harmonically, I propose that holding a smaller diatonic collection is a higher entropic state than the moment when we arrive in full blown pan-diatonicism?

Liquidation can be a dramatic event. When something is held – a theme, a motive, a harmony – its liquidation can be a triumphant celebration of the exhausition of its possibilities. And there’s more poetry – more particular things melting into the sea of less particular things.

Particular harmonic things:

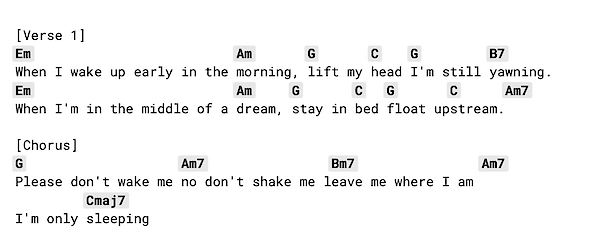

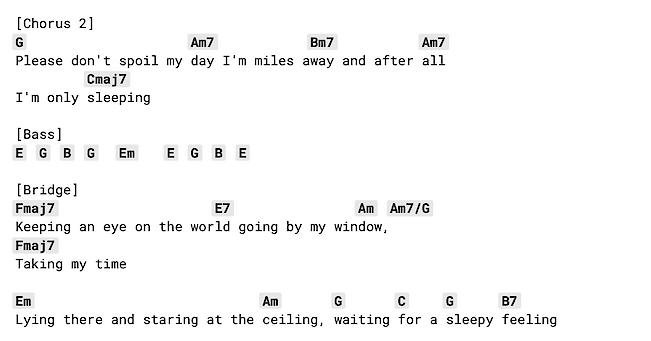

I’m Only Sleeping – The chorus is in the key of “minor 7th chord”. Or, can we say the minor 7th chord achieves middle

1st phrase is 2 minor chords; that color pervades the phrase.

2nd phrase is 2 major chords and a B7 to link back to

3rd phrase and the 2 minor chords

4th phrase – 2 major chords and Am7 looping into the chords that is pervaded by

Chorus – minor7 chords; the minor7 quality pervades the chorus.

Next: the Cmaj7 is a nice turnaround back to E minor, but look what else it does:

Does the bass interlude erase the Cmaj7 quality? Does the C natural stay in the air? When we hear the Fmaj7 do we not get an extension of the maj7 sound? Does the maj7 quality rise to middle ground weight?

Over-foregrounding

There are things that pop out at us and there are things that reach out and grab us by the lapels.

Here’s an example from Fernando Sor, but I associate this trick with Mozart. The #9 – the D# over the C – foregrounds so thoroughly that the 6/4 chrod that follows happens in its shadow. The 6/4 is a very powerful event that jumps to the foreground. The #9 *over-foregrounds*.

Sor makes a point of reinterpreting the D# in his B section. He knows we haven’t forgotten it.

Imagining in a Context

For Ben to sort –

Ben Boretz speaks of “imagining in a context”. I liked that, but I did not fully understand it until I connected it to William James attitude toward philosophy and more specifically James’ anti-idealism.

Boretz told me that he was critical of Babbitt, and Babbitt heeded the criticism. The criticism came fairly early on. (60s?)

–Was that criticism aimed at Babbitt’s beloved logical positivism and did it run along the lines of James’ criticism of positivism and philosophy in general?

–Did Babbitt place too much emphasis on the known and not enough on the knower? The positivists are believers in knowable reality. Boretz & James are perspectivists and relationists. (“Relationist” is Barzun’s replacement for “relativist”. Barzun throughouly debunks the bad reputation of *relativism*.)

Collected in Jacques Barzun’s

*A Stroll with William James*

- James reclassified philosophies as visions.

- Ortega takes thought to be “an action for a purpose.”

- Ortega cites Dilthey’s conviction that philosophy is at bottom a vision.

Finally:

One should say not “I think” but “It thinks.”

do not use the word “hypothesis,: even less “theory,” but

“mode of imagining.” –George Lichtenberg

Brickle, in his last years, lost no opportunity to say how little use philosopny was to him. I knew this was a Jamesian schtick, but it didn’t click for me until a year after Brickle was gone, when I finally put Ben’s “imagining in a context” together with the Lichtenberg quote.

Out of this came Babbitt’s care to be plain spoken, except when he was having fun making his syntax as complex as his musicla phrases, which was just a sideline, a little hobby. Babbitt, whenever he had something important to say, said it in a Jamesian way, or in a simple clear way that showed his abhorence of concepts running amok.

And finally I

Mi Contra Fa

For centuries, we’ve transposed. One thousand years ago, musicians were speaking of “mi contra fa”, where the mi is not in the same gamut as the fa. The formulation concerns

–the mi of so

contra

–the fa of do

If do is C:

–B is the mi of so (G)

–F is the fa of do (C)

The simultaneity could not be thought to exist within the same gamut? This shows great respect for the interval and as we work with the tritone centuries later the interval has not lost is mystique.

This is the principle of the fugue. It is polytonal doings on *do* in counterpoint with doings on *so*.

We hear the mi of so as the same interval as the mi of do, diving down a rabbit hole of interval framing that moves away from the overtone series and JI. The doings begin a thousand years ago.

The temperament came out of the doings. It was not a heady conspiracy to impose a monstrous construct upon music. The irrational numbers of the equal tempered scale are as scary to some today as “mi contra fa” was scary a thousand years ago.

–the twelfth root of 2–

The irrational numbers came long after the doing.

What will moot the argument is good doings in music.

Structural

When does a pitch or a figure or a colleciton become structural? There is no silver bullet.

We uphold that structrual pitches are more local, have *less range* than structural *collections*.

In the Prelude, BWV 997 can we think of the utterly trivial, paper maché circled figures as structural? Can we agree that the intervening 16ths are less structural connetive tissue? Do we all feel the trivial figure gains importance as it is *used*, as it is developed and finally presented in a dazzling tesseration in the sequence? The sequence is built up piece by piece in the circled figures.

Development in isolated bubbles has much in common with Babbitt’s time points and Boykan’s doings in bubbles. Note: a rhythmic figure can contain any pitches. The first two circled figures both have futures. Call them A and B. The A launches a glorious sequence a brilliant tesseration of the A figure.

The B figure returns in the extraordinary and echt *picaresque* augmented 6th chord on beat 3 of measure 15.

It’s *Grimmelshausen Picaresque*.

Adding Pitches

Dina Koston’s quick rehashing of Berio’s approach:

We fix pitches in registers (call this the Varese thing)

Then you add pitches.

Then you start it all over again.

This describes a foreground and middle ground process. We’re only just beginning to see how it can operate on larger time scales.

Kyle Miller’s “Emanation” will soon be released on New Focus and it is a powerful example of the process of adding pitches. And he did it with no influence from Berio or Dina or me. It came to him naturally, authentically.

Subtracting Pitches

K208

Something to do With Phrases

This was the focus of Martin Boykan’s conversations with his students. See the doings in his diatonic bubbles in his Diptych.

Stumbling Blocks & Bitter Coated Sugar Pills

Hole Filling

I felt I was merely hole-filling. The eminence gris said, “in one way or another, everything we do is hole-filling”.

touché

Paper maché

A composer was jealous of my interest in another composer and hurled a bitter-coated sugar pill, saying that fine and very sucessful Crumb protege’s work was “all paper maché.

The composers and alchemists both maintain gnostic traditions such as the scintilla of gold in the dung heap. For an example of a trivial figure developing in a glorious manner, see, Structural.

Nesting

Nesting is a fractal procedure. Wuorinen, with Mary Cronson and Works and Process, gave concerts at the Guggenheim. Benoit Mandelbrot was there to speak about fractals. Wuorinen’s “New York Notes” was featured as a musical counterpoint to the beautiful fractal graphics. That fractals are found everywhere in nature precipitates fractal naturalism. Wuorinen once told me that he’s not a religious person, but he nevertheless experiences a great sense of awe as fractals pervade everything in the universe, “even bad music”.

Nest pitches vs. nested collections

Brickle: “Nested pitches work locallky. Nested pitches operate on small time-scales.”

For some years I was doing the Wuorinen thing, and I gradually came to recognize the strength of Brickle’s distinction. I go down the rabbitt hole of Wuorinen’s example elsewhere. (provide link)

Nested collections can get their teeth into you. What looks like a focal pitch could be a member of a nested colleciton.

We need examples.

The Overtone Series

The overtone series is found in nature.

Is there broad agreement that the hot mess brought upon us through modernist mission creep asked for a radical re-grounding?

I agree that we are working our way out of a hot mess. Vying for culpabiltiy are symmetry death and specificity death?

Spectral and Just Intonation composers are re-grounding their work in the cold hard fact of the overtone series. This brings with it a backlash against temperament. The piano is vilified as the most tempered of instruments.

The *doings* from which the terms in this glossary arise have resulted in tempering of intervals. There’s now a heady backlash against these doings becasue they pull away from JI and from the purity of the overtone series.

I’m putting forward the terms in this glossary as a defense of those doings that are under attack. I’m putting forward terms as excrescences of doings.

Dina Koston’s perspective – “all of my music can be derived from the overtone series”. Her owning of the overtone series makes me suspect that she might have worked her way to the spectralists. Her music assumes equal temperament, but she often ended with the overtone, calling for a JI flat 7th. See her *Distant Intervals* and *Quartet for Strings Bowed and Plucked*.

Isn’t Koston simply avowing that 12-EDO comes from the overtone series through centuries of fugueing – polytonal framing?

Milton Babbitt said in my hearing that the overtone series is problematic as a grounds for music. Nevertheless, I cannot imagine that he would disagree that the overtone series begat 12-EDO.

He was happy to say that his guitar duo does not sound tempered.

(Dean Drummond, the late curator of the Partch instruments, said the guitar is very Pythagorean, regardless of the attempt to temper the frets.)

Babbitt could have been alluding to a logical empiricist objection to the idealization of the overtone series. But the more likely interpretation is that he was defending *transposition*. An ideological hatred of temperament is an attack on transposition, which has been central to our doings for a long, long time.

Each pitch in the overtone series is absolutely unique. Or consider minor thirds in just intonation. One can insist that the minor thrid from 2 to 4 is a different minor third than the ones between 3 and 6; 6 and 8. Composers pun with those not-quite identical intervals as if they are identical and in practice they gradually become identical.

For centuries, we’ve transposed. One thousand years ago, musicians were speaking of “mi contra fa”, where the mi is not in the same gamut as the fa. Speaking of “mi contra fa” implies transposition.

See Mi Contra Fa

The formulation concerns

–the mi of so

contra

–the fa of do

If do is C:

–B is the mi of so (G)

–F is the fa of do (C)

The simultaneity could not be thought to exist within the same gamut?

This is the principle of the fugue. It is polytonal doings on *do* in counterpoint with doings on *so*.

We hear the mi of so as the same interval as the mi of do, diving down a rabbit hole of interval framing that moves away from the overtone series and JI. The doings begin a thousand years ago.

The temperament came out of the doings. It was not a heady conspiracy to impose a monstrous construct upon music. The irrational numbers of the equal tempered scale are as scary to some today as “mi contra fa” was scary a thousand years ago.

–the twelfth root of 2–

The irrational numbers came long after the doing.

What will moot the argument is good doings in music.

Unity

two attractive disunities

Carter’s beloved all-trichord hexachord is a packaged disunity. Its subsets repel each other.

Maybe the same can be said for the diverse themes in Schoenberg’s op. 9, where each theme is of a different interval cycle, each with distinct viscosities that don’t mix. (See The Grain of the Wood.)

Music survey courses in the 80s taught unity as a good thing and as a way to expalin the motivation for 12-tone music, which always provoked gasps of disgust from the class. The row provides intervalic unity.

I asked Akemi Naito about Schoenberg and she said she likes the pre-12 tone work. I disagreed with her becasue I adored the 12-tone stuff, was utterly devoted to it. Moreover, I felt and still feel that Schoenberg was answering a need to find an overarching order for the far-flung harmonic experiments of his free-atonal work. Schoenberg writes all that, spells it all out, but I felt it.

Schoenberg’s classical impulse reminds us of Bach’s cosmic order. Bach’s predecessors like Buxtehude and Froberger were supremely inventive and daring. Bach wanted to embrace the invention and caprice, but he wanted to order it. A most wonderful example is the minor-major7 chord that opens the Saraband of BWV 995. That’s a very memorable thing and so when it appears again, in the cracks between gestures in the Gavotte, we notice it. Both instances of the minor-major7 chord are in the A section. Bach’s sense of cosmic order is that what happens in the A section will be inverted in the B section, reflecting the macrocosmic structural doings in binary form – A sections goes I to V; B section goes V to I. And so therefore in the B section of the Gigue the inversion of the minor-major7 chord must manifest. It does in the very last dying gasp of the suite – an augmented-major7 chord.

After some decades of composing and thinking about these matters, I came around to Akemi Naito’s position, without in any way revising my passion for the 12-tone work. An ideology exists in a separate sphere from a passion. The passions persist despite the ideology.

So many of Schoenberg’s 12-tone works sport the very tight family of interevals found in what the Princeton people called the E-hexachord. The E hexachord is the augmented scale, the 1, 3 cycle. That’s too unified. But despite an ideological objection, each particular case wins me over.

Op. 9 offers rhythmic unity. The rhythm of the whole-tone melody is very similar to the rhythm of the rising 4th theme. Unity can be in intervals or in rhythms.

Perspectivism

The Hipster Industrial Complex

Hipster: “My mass-produced, industrialized culture is better than yours!”

A gag that was going around.

Barzun on Henry James—

“…..For millennia the ideal of unity prevailed, as it still does in two thirds of the world. Pluralism could not succeed before the invention of social arrangements that would allow needs and desires to be satisfied in more than one way; and it had to wait for a reeducation of the feelings that would enable the individual to accept some at least of his neighbors differences in politics, religion, pigmentation, and taste….. this reeducation is obviously more difficult or less, depending on the individual’s philosophical outlook and moral training. Everybody is by nature an absolutist and imperialist: my view is right and shall be yours. Perspectivism must be taught in the teeth of this simple animal, faith, and that teaching is still rudimentary. It does not yet include the art of finding the right words for stating rival truths in mutually acceptable ways. Such an art would bring about not simply a higher degree of tolerance, but a new kind. At present, toleration means indifference between the parties, or division of territory, actual or intellectual, among absolutists none of whom is strong enough to impose his rule any farther. That is our present pluralism.…. it still comes easiest to imagine those who differ from us as lost in a fog of illusion, perhaps dangerously so for us. We create monsters of error and indeed enjoy doing it. A pragmatic search for opposite truths, made acceptable by being more exactly, the limited would create both a new, kind of peace and a new kind of pleasure…..It is clear from James‘s letters and his friendships that this sort of pleasure was native to him.”

Mutatis Mutandis

Concepts get out of hand; values overstep their bounds; mission creep ensues.

What composers are doing, perhaps, is revising the concepts on the fly (mutatis mutandis), to the unique situation at hand.

Concepts are not bad. James & Barzun do not make that claim. They argue for strength and relevance.

“hard clear words”

“Truths” that “work”: James argued that the test of a truth is “the conduct it dictates and inspires”

Barzun

“Knowledge that leads to doing something”:

Instrumental Politics

Trivial: soli and sub-groupings. Babbitt’s Swan Song No. 1. All the instruments get a solo except violin. Many wonder why not violin? And then there can be any number of duos, trios, quartets, quintets and tuttis.

More interesting: *agencies* – “Aranjuez” cadenza; “1918” 027 move.

The guitar and orchestra arrive together in a “place” – C# minor, but then the orchestra steps away by minor thirds (as I recall; I must look at the score again). This leaves the guitar *alone* in exactly the spaghetti western, wabi-sabi sense of “alone” – a picareque sense of *alone* – as it begins its cadenza in C# minor.

Transitions

If one thing has nothing to distinguish it from another, no transition is needed. It’s a free-for-all. So one might *hold*. Keep something in place. The harder it is to dislodge, but more successful you’ve been at holding it firm. And when dislodging is the aim, how dramatic can it be, and how well was that big moment made inevitable?

Joan Tower often keeps the body of a movement entirely in the octotonic scale, bringing in diatonic harmonies at the end. A big broken symmetry.

The Grain of the Wood

Each is a distinct grain of the wood, a distinct *nap*. Better: each has a distinct viscosity. Like being in a room with a certain aroma and lighting (Claire Heldrich, talking about Carter’s Syringa).

chromatic – a through cycle

whole tone –

3-cycle (diminished 7 chord) implicates the octotonic (diminished scale - diminished 7 chord with passing tones)

4 cyle – implicates the whole tone scale, but also the augmented scale

5 cycle – a through cycle

1, 2 cycle – octotonic scale

1, 3 cycle – augmented scale

1, 4 cycle – a through cycle; each adjacent pair of semitones is a signature of a diatonic septachord

these need more doing:

1, 5 cycle – a color more than a viscosity?

1, 6 cycle – a through cycle; weird similarities with the 1, 4 cycle; the Lydian counterpart of the 1, 4 cycle?

[There’s a passage in Alexander Tansman’s Suite in Modo Polonico which prolongs the Lydian in a manner that might happen over a 1, 6… framework.]

Broken Symmetries

What Wolpe taught Feldman and Brouwer

Wolpe, Feldman, Brouwer

Instate a symmetry; break it

see “Ghost Tones”

Open symmeties

a cycle that goes through all the pitches before repeating.

1-cyle

5-cyle

7-cylce

11-cycle

Closed Symmetries

symmetries that loop back upon themselves before going through all 12 pitches

octotonic scale is the 1,2 cycle

3 cycle

French Augmented 6th subset – link to whole tone

minor 7 chord subset – link to diatonic

Augmented scale - 1, 3 cycle

whole tone scale - 2 cycle

Open Cycles

chromatic - 1 cycle

diatonic - 5 cycle

Bumps

An intrusion, something extrinsic to the proceedings that jolts us out of our complacency. If used strategically, a bump might point to a breakage?

One cannot make a bump without establishing something smooth.

Cloned Themes

A cloned theme “extends” some intervals.

A cloned theme can *prolong* a collection.

Kupferman - a group of themes in Balinese Pentatonic. That’s problematic in an instructive way because scales are very liquid and holding things is pre-liquidation.

Sonata form - very broadly, a group of themes in the same key might be cloned themes, let’s think of examples.

Princetonian - a group of themes (tune/harmonies) that *hold* (project) the same chord (collection or “set class”).

Bildung

Wilhelm Meister arrives at a place where young people are on horseback developing bildung.

Let’s think of “all we have is pictures high”, from Emerson’s poem, as “all we have is bildung”.

Greenbaum’s “Wild Rose, Lily, Dry Vanilla”

WHERE the fungus broad and red

Lifts its head,

Like poisoned loaf of elfin bread,

Where the aster grew

With the social goldenrod,

In a chapel, which the dew

Made beautiful for God:—

O what would Nature say?

She spared no speech to-day:

The fungus and the bulrush spoke,

Answered the pine-tree and the oak,

The wizard South blew down the glen,

Filled the straits and filled the wide,

Each maple leaf turned up its silver side.

All things shine in his smoky ray,

And all we see are pictures high;

Silence

Stefan Wolpe was presiding over a gaggle of composers. When Wolpe arrived in the US he was a rock star, as was Krenek and others. How would his knowledge take root here?

Meyer Kupferman went to HS of M&A with Morton Feldman, a key Wolpe student. Feldman invited Meyer to the gathering. “Maestro”, he asked, “do you ever compose with silences?” Wolpe responded, “one must *earn* the right to compose with silences.”

Likewise, noise and microtones. Our concern is not that silence, noise & microtones *must* ruin music. Our point is that those don’t have to ruin music. Those will not ruin music if the goal is –

silences *and*……

microtones *and*….

noise *and* ….the tradition – the unlistable musical principles that work, unlistable becasue new ones are constantly being discovered.

Anything as vague as, “the tradition” can only be protected and cultivated by a priesthood. And it is. Here citing one sage, Wolpe.

Another priest, Taruskin, has made this point. I suspect Taruskin’s sense of “maximalist” as a slur gets to my concern if Taruskin means, “more is not more”.

Taruskin, if this is his point, jives with anti-reductionist Wendell Berry and Hermann Broch and William James.

Caveat

We love music & art that is perched near an abyss or a black hole; we love art for art’s sake. It was Broch that makes so clear that art for art’s sake is making an absolute value of something. That leads to totalitarianism. Broch is all over this in his essays and novels. An absolute value is like a zero in the denominator. Broch was taking a clue from such as Maeterlinck by adopting the symbolist and/or romantic notions of infiity and death or death as infinity. Some of our favorite work comes from that space. Think Webern & Georg Trakl. Decadence is death as a positive aesthetic value. Broch’s infinity becomes a critique of romantic impulses as they plunge headlong into totalitarianism.

The uptown people are Yellow Book Decadents, downstream from the romantics and in the thick of the symbolist ethos.

Broch is right, but many of us have grown to love l’art pour l’art and everything 1890s. A concept that will go amok later is often at the heart of work that is very dear to us.

I say to the ghost of William James: “OK, I am with you in your anti-idelaism, but I love blue flowers becasue good people like Novalis and Hermann Hesse have taught me to love them.”

An anecdote about Kupferman and Wolpe. I heard the story from two different sources. Milton Babbitt told it like this. Someone was stealing Kupferman’s music. Kupferman & Feldman confronted the man and a fistfight ensued. Police came. Feldman & Kupferman needed someone respectable to bail them out. They called Milton Babbitt, who obliged.

I broached the story to Babbitt because I’d heard it once from Kupferman. I was curious to hear his version of events. But when l mentioned Babbitt’s version of the story to Kupferman, he was embarrassed, saying, “I would never resort to violence!” Kupferman & Feldman were street kids.

Maximalist

Wuorinen & Babbitt proudly adopted “maximalist”.

Taruskin’s negative sense of “maximailist” jives with our complaints about “more is more”, concepts running amok and vicious intellectualism. I take Taruskin as an ally in my fighting against what I feel is “modernist mission creep”.

Ultimately, my most obsessive heros I hold not guilty of mission creep, on the strengths of their doings and despite their scary surfaces.

Getting Claudio’d

Claudio Spies was one of the most brilliant of the Princetonians. Milton Babbitt once told me that Rolf & Claudio were his favorite composers. Rolf Yttrehus and Claudio Spies. I liked Claudio, but Claudio hated everyone.

Claudio could be a pill.

First Variety

A complaint is leveled at your work regarding an aspect that is on the very outer periphery, a not-even-wrong statement takes nothing away from the specific work or your work in general, but proves how unlikely it is that anyone will get to the very heart of the matters in which your work is engaged.

Second Variety

Someone says very neatly, concisely, what you had set out to do, perhaps with more clarity than you would put it yourself, but expressed as if it’s a bad thing.

Anecdote

For some reason my son Henry was with me for Claudio’s retrospective concert at Taplin Hall at Princeton in the early 00s. That’s when I discovered Claudio’s wonderful piano solos. They struck me as attempts at 12-tone cocktail music. And this was the day when my son Henry said to Milton, “My dad’s a better composer than you.” Milton laughed and asked, “what about you”?

The first piece Frank Brickle wrote for me was a suite for guitar solo with a punny title – “Child Orpheus”. Claudio was at the premiere of *Berceuse* in the 80s and he Claudio’d it.

Bitter-coated Sugar Pills

Getting Claudio’d can involve a bitter-coated sugar pill.

Many criticisms are bitter-coated sugar pills. Take some not-even-wrong statement and present it in a way that sounds damning.

A composer once derided another composer by saying their work is all *paper maché*. The syntax and tone felt like an insult. But ultimately, that’s a bitter-coated sugar pill. Music is wonderful paper mache. Triads are paper maché.

Bach and Scarlatti – what begins to feel like the truly structural melodic material can sometimes be utterly trivial. – scale degrees or chord tones: 3 2 1.

Reference Passage

Brickle, Lansky, Stravinsky, Brahms

Brickle put forward the opening of his Farai un vers as an example of a reference passage in the manner of Lansky and Stravinsky.

AI regurgitates some previous attempts I’ve made to document the concept of a reference passage as Brickle applied the concept:

Yes, the term “reference passage” in relation to Stravinsky appears in the context of discussions surrounding composer Frank Brickle and the use of compositional structures like arrays in modern music.

According to a tribute on the Rogers Shapiro Fund website, both Stravinsky and Paul Lansky are mentioned by Frank Brickle as composers who “build out from a reference passage”.

In this specific context:

• The “reference passage” is described as a way to move beyond the limitations of strict, “Platonic” arrays or rows in serial music.

• Brickle felt that array music often “mistakes its job” and that an array must become a “reference passage” that “does what music does”.

• The discussion suggests the reference passage is a more fluid, musical concept compared to the potentially rigid structure of a pure array, implying a method of composition that prioritizes musicality and development over strict adherence to a pre-defined abstract structure.

I don’t even trust that the opening of Farai un vers comes from an array. And it matters very little if it does or not. Brickle may have known I was fascinated by arrays at that time and allowed me to think his reference passage came from an array.

This needs sources

Stravinsky/Krenek Rotations

See Jonathan Dawe’s work

Symmetry Worms

Sometimes we catch movement through a symmetry and continue it in our mind. That this happens supports the theory that we can displace a note that’s never heard – ghost tones.

Sonata Form

Cloned themes hold the same chord quality (aka set class), as theme groups in Sonata-allegro expositions can hold keys.

Schenkerisms

“One of the most amazing instances of “algebraic” game,. which is also “vicoious intellectusalidsm,” has held say in music theory for over half as century. It is the so-called “Schenker-analysis,” names after the German Heinrich Schenker (1868-1935), With his *Urlinie* and other concepts one can reduce any piece of music to a formula of the utmost simplicity. The method takes no account of melody, rhythm, meter, timbre, or register. These aside, the formula yields “the essential music.”

This is a footnote in Jacques Barzun’s *A Stroll with William James*.

I am convinced that we must be wary of vicious intellectualism, but Schenkerian analysis is not an example. It’s a way of looking at the large body of music that Schenks.

The method *does* take melody and register into account.

In other passages in Barzun’s book, Barzun defends concepts when they are properly delimited. He even defends philosophy.

I got anti-philosophy from Frank Brickle, which I assumed came from his love for William James. Barzun and James are not anti-philosophy, anti-concept, anti-theory.

They are against vicious intellectualism, which Schenkerian analysis is not, but can be, as any concept, theory, philosophy can be.

As a way of looking at music, it can provide an impetus, a starting point.

What was Brahms thinking when he wrote –>

C# B D — C# B (high) A????

And he didn’t need Schenker to think that way.

///////////////////

Holding II

Perhaps what you hold becomes structural. What is held for a short time is foreground; what is held a bit longer is middle ground; what is held for a long time is background?

Barzun on William James:

“So we are not spectators, watching the film reality as it unrolls; we are participants of events, confluences, conjunctions that divide themselves into ideas tinged with feelings, on the one hand, and objects endowed with qualities on the other, depending upon the connections of each. These we discovered pragmatically. We find, for example, a kind of fire that Burns and we call it “real“; and again, a fire that does not burn, which we call the idea of fire. For the infant, there is no distinction; for the adult, both are in fact equally real, though practical interests have given us through language, a bias in favor of objects.”

Barzun wrote a letter of recommendation for Charles Wuorinen. Barzun would know how William James’ perspective differs from Husserl’s. Husserl is more of an idealist?

American composers take Schenker in a more Jamesian light. How vastly different James is from the idealists is something that Barzun understands very well.

Liquidation

Liquidation can be a dramatic event. When something is held – a theme, a motive, a harmony – its liquidation can be a triumphant celebration of the exhausition of its possibilities.

Brickle complained about Sibelius, saying he *begins* in a state of liquidation.

Critics of minimalism might say the same thing. Holding can be thought of as postponing the liquidation to pan-diatonicism.

Rhythmic liquidation – when the rhythmic motive boils down to basic stuff, into a free passage so scales and arpeggios.

I have a hands-off approach to Sibelius but I’d apply Brickle’s objection to much music. Perhaps I’d level this criticism at pan-diatonic music that never breaks down the diatonic into subsets with more profile, as the Beatles do here:

I’m Only Sleeping – The minor 7 chords.

Or as Bach does here, allowing the redolences of 015 to prevail for a spell.

BWV 996 Allemande

Or the Brahms cello sonata.

Or Joni Mitchell’s The Banquet.

Foreground

a gesture, a riff, a tune

Middleground

When there is something like a chord progression, the movement from one chord to the next is a middleground move. When there is a palpable harmonic rhythm, there is a middle ground.

Background

Large scale doings of a work

Brahms & before – binary form and sonata form doings –

modulation

After 1918 – see “The Op. 9 Thing”

Prolongation

Elaboration

Extension

Sufficiency

Structural sufficiency. What makes an insufficient background. When transposition is everywhere in the foreground, it is no longer a sufficient basis for a background, for a large scale structure like binary form.

Sufficiency

Still fuzzy on this. This is still in the works.

It occurred to me as a thing when considering the question of modulation as a large-scale structural feature. When the foreground is already dense with transposition, transposition becomes insufficient as a large-scale structural element.

The 20th Century saw many wonderful solutions to this problem. At the same time, for as many solutions there are hundreds of demonstrations of the problem. That this hot mess eclipses the successes accounts for much of what I’m calling modernist mission creep.

Hyperlydian

Bartok & Indian classical music. Harold Meltzer’s “Doria Pamphili” and Kentner Anderson’s “1918”

Circle of 5ths Transform

Bartok

Of Course, Coursing Again

Ziguezon

mi contra fa

see Lydian timeline

diatonic collections with tritones and diatonic collections without tritones are two discrete universes.

Ghost Tones

Best to show the examples in the work of the éminence gris.

Genius Loci

The Creation, a Towneley Mystery Play

Displacement

Brickle tried to re-program my idea of what a displacement is. Is it the crucial notes in the breaking of a symmetry? Brickle played the

Stravinsky Octet. The first contrasting section achieves a displacement.

Brickle recounted the story of Milton Babbitt’s first meeting with Sessions. Sessions asked, what is your goal? What wouild you like to be able to do? Babbitt mentioned the Stravinsky Octet. Sessions said, OK, that should be easy.

Third Stream

Gunther Schuller, Meyer Kupferman, Stan Kenton

A-Roll and B-Roll

I cite here Brickle, for the cinema analogy, and I’ll cite Dave Eggar’s great example from his work with Paul Simon.

A-roll is of our full consciousness. B-roll operates in various depths so of unconsciousness or subliminality.

To make a longer work, there must be B-roll. B-roll is the music that allows the listener to recover. But how wonderful to plant seeds while the listen is recovering – Beethoven developing material in his codas, is perhaps a good example?

Cellist Dave Eggar worked with Paul Simon. Dave reported that PS would ask for 100% focus in one place; looser 60% in another place. And this intensity and relaxation is also seen in PS’s lyrics. “Laughing on the bus” is B-roll. “I’m empty and aching and I don’t know why” is A-roll.

Liquidation can be B-roll.

Del Tredici’s Herrick’s Oratorio begins with a motive, “I do believe”. He repeats is until we begin forget what he’s saying–reduction to phonemes, and we gradually come back to the words and suspect that he needs to convince himself that he believes. He repeats it still further until we’re convinced that he is utterly stricken with doubt. When the motive liquidates we are treated to his reserves of modernist devices that he’s stored up since his bad old modernist days and we feel his intense wonder and awe. His childlike joy in the universe comes across in his modernisms.

William James –

“If the word “subliminal” is offensive to any of you, call it by any other name you please to distinguish it from the level of full sunlit consciousness. Call this latter the A-region of personality and call the other the B-region. The B-region, then is obviously the larger part of each of us, for it is the abode of everything that is latent and the reservoir of everything that passes unrecorded or unobserved. It contains such things as our momentarily inactive memories and it harbors the springs of all our obscurely motivated passions, impulses, likes, dislikes, and prejudices; in genreral all our non-rational operations come from it. It is the source of our dreams and apparently they may return to it.”

A problem with array music, Milton Babbitt’s and mine, is that the moment to moment doings are more uniformly demanding of our attention. And yet the music does breath, but it breathes in such a weird way that some people don’t know they’re allowed to reaction.

Another uptown problem – people don’t know when to laugh.

Delightful Trivialities or Irrelevancies?

The Eminence Gris passed his love of JK Randall’s thing – “delightful irrelevancies”.

Delightful trivialities can be earned, like silences can be earned. It can be a stand-alone utterance whose meaning has been established through previous hard work and development – a condesate or a crystalization of some meanings that the work has established.

Lydian Timeline

Perotin & Reich

Double leading tone cadences

tritones

mi contra fa

binary form A section

The film music that happens when cute monsters are prancing.

The Mother Nature’s Son Thing

The very opening of Mother Nature’s Son extracts the part of the song wherein the music turns on a dime from mock-sincere hippy to skiffle clown. Sincere hippy is in the walk down from B to G#, landing on a Tristan Chord. When the low E appears in the bass, the minor-third heavy Tristan Chord turns on a dime and becomes a major second heavey dominant 9 chord. The song has great fun with this.

What’s astonishing is that this move implicates an impressive family of late Romantic, Impressionistic and Pre-Raphaelite works where the dominant 9 chord is knowingly circulated as the hermaphrodite that is 4/5ths octotonic and 4/5 whole tone. It is also 4/5 dominant 7 chord and 4/5ths Tristan Chord. Ravel’s Pavan for a Dead Princess slides dominant 9th chords around by whole steps, horizontalizing the dominant 9’s whole step-heavy verticalities.

The Tristan Prelude famously traverses between the Tristan Chord and the dominant 7. Bernstein pointed out that it always succeeds in dodging the fully diminished 7. Eric Chafe, the Wagner specialist, in a long conversation in Waltham one evening when I was a guest at his house, assured me that Wagner was interested in manifesting horizontally the Tristan-Dominant7 harmonic inversion.

Together with the Mother Nature’s Son move, let’s also consider related moves.

–The Leo Brouwer Cuban Landscape with Rain move also involves the appearance of the guitar’s low E.

–Davidovsky’s all-intereval tetrachord move. I don’t yet understand it, but in almost every work he plays a trick wherein a harmony is held, static, in upper registers until a low note appears that recasts the material above. Arthur Krieger and perhaps other Davidovsky people make this their own. I first noticed it in Arthur Kreiger’s “Suitable Attachements”.

See Kentner Anderson’s “Ziguezon” and “Simple Composition”

The Augmented Scale as a background and a foreground

It’s a background in Brahms

It’s a foreground in Schoenberg

Brahms to Schoenberg is small step

Inversion

If you don’t care about it, study Bach’s 5th Cello Suite, aka, 3rd Lute Suite.

BWV996 and Brahms op. 114

Tristan Prelude & Eric Chafe

Brahms–Schoenberg is a small step

The Tone Clock

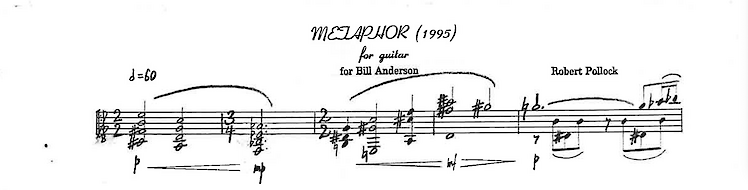

Dutch composer Peter Schat was a hero at Aspen when his opera Houdini was produced in the late 70s. Toward the end there was a photo of Schat enthroned on a big rock in Haleakala Crater on Maui, a guest of his friend and colleague Robert Pollock. We’re looking for that photo.

I know the tone clock dynamics through Robert Pollock, who found Schat’s thinking very powerful, answering questions he felt were left unanswered by the Princetonians.

Schat assinged each trichord to an hour, and he noted the “driving interval” of each trichord. Transposing the hour by the driving interval will complete an aggregate neatly. And Robert explained that one tetrachord fits neatly into this scheme, as we see in his “Metaphor” for guitar.

“Metaphor” for guitar may be Pollock’s first and purest tone clock piece. Here’s the reference passage. The piece elaborates the elements set down in the first 3 bars – 0279 is one of the hours and it is driven by 4s (transpositions through the major 3rd cycle completes an aggregate); 048 is another hour and it is driven by 5s.

This is very chunky, and Pollock never since expressed the concept so nakedly as he did here.

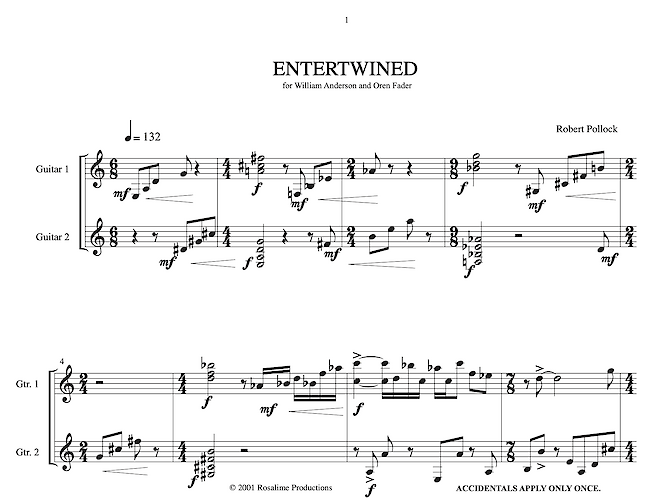

Entertwined is a masterpiece. The reference passage shows an interest in assymetries, with nothing breaking down into the neat, but square elements seen in “Metaphor”. The underlying symmetries are beneath the surface, not in full display.

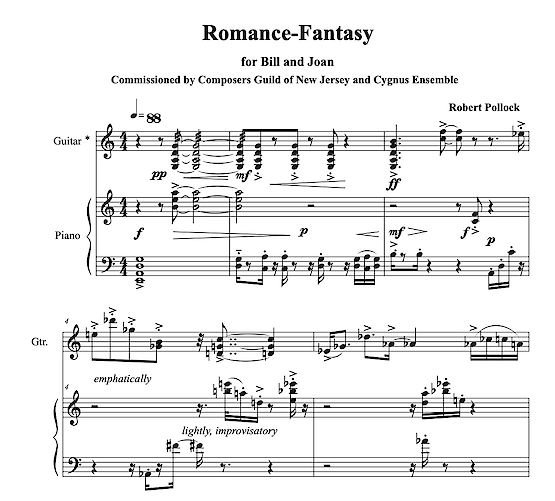

In “Romance-Fantasy” for guitar & piano, the Schat symmetries are still further in the background, and play out over larger time spans. There’s a clearly perceptible phrase rhythm – land in the 4th chords, weirder things through the mid-phrase. The weird things are also very rhythmically syncopated. The return of the tonal harmonies coincides with an *un-syncopation*.

The return of the tonal harmonies at the ends of big phrases coincides with an *un-syncopation*.

Pollock was interested in this approach for his guitar music because of the tuning of the guitar, in fourths. I like the harmonies of his guitar pieces because the surface is pervaded by diantonic harmonies and their adjacencies. 0279 is the harmonic heart of this group of guitar pieces.

We talked about the tone clock with Babbitt. He scoffed, “oh, the 12 trichords”…..he was all over that decades earlier. Babbitt was interested in all-trichord rows. Swan Song No. 1 is based on an all-trichord row.

Simeon ten Holt

Op. 9 Thing

How this relates to the re-packaging as “set class”

How does this relate to Prolongation, Elaboration, Extension?

Chord quality supplants modulation as the large scale structural element. Milton Babbitt, at his 90th birthday concert, pointed out that Op. 9 treats all the interval cycles. Babbitt’s Swan Song No. 1 springs forth from an all-trichord row. The 12 trichords have an interesting relationship with the interval cycles.

The Op. 9 Thing is hundreds of years old. It’s very clearly at work when a minor key works puts forward the relative major as the secondary key.

But we also gradually start to realize that modulating to the dominant involves a Lydian move. It feels Lydian.

But the Op. 9. thing is different. How would we keep that Lydian feeling going? See Alexander Tansman’s very Pre-Raphaelite Suite for Guitar. See Schubert’s F Minor Fantasy for piano 4-hands. See Led Zepplin’s No Quarter and Dancing Days.

And in the same time scale, Bach’s Prelude BWV997 holds dominant b9 almost the way the blues progression holds the dominant 7.

Holding tight and holding loose. Brickle advocated for Webernian aggregates – holdilng tight. I could never do that. I like internal breaks that make the return of the held chord quality (collection) a welcome return.

The earliest instance of the Op. 9 thing that I’ve run across is Bach’s Allemande from BWV 996. We must postpone a longer discussion of the well discussed feature of BWV996 as it relates to its third structural key, G major. Here, G major appears in 015 colors. In the 2nd beat of bar 3, we see in miniature what Brahms does in his cello sonata.

Put a C on top of an e minor triad and enter the 015 world. The little swoon in the 2nd and third beats of bar 4 is a righting of the harmony on beat 2 of measure 3.

Joni Mitchell “The Banquet”

The Op. 9 Thing is to hold something for a bit, long enough so that after a departure there can be a sense of return.

I make the linkage from 045 to 067 in ;my guitar solo Poema armónico I.

015 and 017 are adjacencies.

Ponce Sonata prolonging 027

More on 017.

Led Zepplin’s Houses of the Holy sports 017s in “Dancing Days” and in “No Quarter”. In both examples 017 has a sinister quality. Of all the harmonic phenomena on the album, the 017s might stand out the most. If there are some 014s, we will not be surprised because they are bluesey.

Schubert’s Fantasy in F minor, 2nd theme, is all about 017.

Brahms op. 88:

C - - F | E - F - |

The piece is about major 7 chords and the augmented scale is the structural backbone of the piece – scale degrees 1 and 5 and b6 are the structural areas through the major 3rd cycle.

4 Op. 9 and Holding

Before 1918 music was holding a triad.

–projecting a triad

–extending a triad

Now, a few *hold* diverse trichords (including triads), tetrachords or hexachords.

Milton Babbitt made a point of telling me that he is very interested in Schenker. It is the tradition that he attended in his most bizarre and idiosyncratic way.

Like Schoenberg, Babbitt extended hexachords.

He also was careful to explain to me that after WWII Sessions sent him to Europe to collect extant Schenkerians. What did they want to do with them? I didn’t delve into the master plan.

The music is no longer thinking solely about projecting the triad through the work, but another larger collection, such as we see in these examples –

015

Bach BWV 996

Brahms op. 88 (2 examples)

Brahms Sextett Op. 36

Brahms op. 38 cello sonata

Joni Mitchell The Banquet

-7 chord

Sor Study in D

Mertz Lied ohne Worte – *organic* – harmonic seeds

016 & 0167

Berg Sonata op. 1

Schubert F minor Fantasie

Liszt Nuages gris

Led Zepplin Dancing Days & No Quarter

Steely Dan Rikki Don’t Lose That Number –

B D# G# A Dnat G# A E

The Rikki lick holds 026.

027

Ponce Sonata for guitar and piano

Alexander Tansman Suite in Modo Polonico holds a Lydian

through the house of mirrors.

Op. 114 Thing

Boil two entities down into a semitone

Op. 15 Thing

Bb over /D pedal, then later, E major over D pedal.

see

Kentner Anderson’s “1918” and Frank Brickle’s setting of Merlin I

The Chromatic Tetrachord Thing

a Davidovskyism

Muck around within a chromatic tetrachord, building up tension until a crucial moment when the you break free and heroically resent the major third.

see Greenbaum’s Nameless

But this is a thing. Look for it in Eleanor Cory’s music. and other Davidovsky people.

I tried it in “1918”.

Overdetermination

We carry the sense of “overdetermination” as it appears in psychological to music. Any musical work that makes it to the double bar is overdetermined. The doubters and nay-sayers may succeed in straightjacketing the composer. Some composers are more complacent than others. Those most keenly aware of the high stakes are cautious, seeking overdermination, seeking a counterpoint of elements that strike the composer as determinants, with one element shoring up the next.

Values that are determinant can cast a passage of music in a rosy glow and so if the value is a fantasy of the composer and not a value that translates to others, the composer could fail. Overdetermination overcomes doubt. A project will overcome doubt and move forward when there is an overwhelming confluence of positive determinant values.

Gatherings

Wuorinen’s Psalm 39 – at the word, “gathering” Wuorinen gathers pitches from three utterances.

Anderson pop songs and folksongs

What Wuorinen does happens all over my pop songs and folk songs.

Schoenberg op. 27 #4 – at the end there is a moment that feels like the Mixolydian ending of a binary form. It’s a dominant 9th chord with no 5th and it is created by gathering the 3rd note of each of the 4 forms of his tune.

Time Points

duration rows

vs

Babbitt’s time points

In Babbitt’s approach does something akin to what phrases do. Call cadences and periodic phrasing the traditional approach to time points. “My endings are my beginnings” – the phrase endings don’t have to be at the ends of phrases. Babbitt’s time points create things anywhere. They can recur on different scales. Swan Song No. 1: the eighth note triplet in measure 1 recurs later (many times) as a quarter note triplet. We remember that rhythmic figure and what happens in it. It usually holds 015, but in one instance that is displaced by 027.

The Midphrase

sometimes things happen midphrase that makes us feel the enterprise was worthwhile

The iii chord

Penny Lane

I Will

Julia

Across the Universe

Here There and Everywhere

Stay put, or point toward a way out?

Webernian approach stays put. Holds the fort.

pointing toward a way out – Kentner Anderson

i – IV

Debussy

Beatles – Here, There & Everywhere, Yesterday

Brickle

Magic Square

the Boulez trick

Arrays

Metavariations

Pitches

Dina Koston on Berio’s approach to compositon:

–Set pitches in specific registers,

–add pitches

Partitions answer these questions about the Berio business:

Set enough pitches in place and one gets a pitch field

When to re-assign?

Rate of reassignment?

Webernian Trichords

a limited palette leaves the possibility of expanding the palette

Superarrays

Not merely a counterpoint of arrays. The usefulness of the superarray is in the possibility of converging on a focal harmony. The focal harmony should be mixed up witht he inversional pairs, which are invariants. They change places in the M5 arrays, but they do not go away.

Partitions and multiply partitioned arrays

My Morphine

“1918” partitions

Fiefdoms

One rehearsal to the next left me feeling that the previous composer, meeting the next composer, would annihilate one another like matter & anti-matter.

They formed tenuous alliances through their little fiefdoms –

The Group for Contemporary Music

Composers’ Conference

Theater Chamber Players

NYNME

Speculum Musicae

Cygnus

New Music Consort - toured with Judith Pearce and Martin Goldray

Bang on a Can

Ekphrasis

I take “ekphrasis” in a more general way. For me it is more than a poem about a painting.

Hellenism-Vergil and Petrarch

What makes us feel a culture is charming in its tidiness, completeness & *comprehensibility* tends to come from our distance from it.

Vergil, and later Petrarch and Vico lasso the polyglot past. This is ekphrasis.

Vergil lasso’d polyglot Greek. Johann Gustav Droysen & later Winkelmann called the result *Hellenism*.

Petrarch had a volume of Cicero from his father. Barzun claims:

“The work filled his mind with ancient facts and ideas; a trip to Rome fixed his vision. For there he saw and marveled at the antiquities, tangible remains of a culture once alive and complete.”

My gloss on Vico — *one can empathize with a culture not one’s own*. Isiah Berlin loves Vico because he finds in this empathy a way toward pluralistic values. He & Barzun were both fascinated by the ability in some of us to entertain values that are mutually incompatible.

But the other examples show it goes beyond empathy. We are charmed & we feel nostalgic.

Sir Walter Scott & Goethe’s *Goetz von Berlichingen* — the castles became quaint.

The British Invasion

Perhaps Zappa & The Beach Boys helped with the British Invasion and the creation of groovy?

The Zombies’ “She Wasn’t There” is early groovy.

The early Beatles engaged in their own form of doo-wop & rockabilly. Groovy came from purging doo-wop & Motown? Did a commitment to psychedelia help purge the doo-wop?

Song Dynasty

In China there was one Dynasty that was nostalgic for a previous. I felt that was an intramural time-ekphrasis. From Simon Leyes *The Hall of Uselessness*: The Song Dynasty was a disaster, “a menaced world, a mutilated empire…. The Chinese faith in the universality of their world order seems to have been deeply shaken by the permanent political military crisis, resulting from the foreign menace, and it is in this particular context to that, for the first time in Chinese history, a massive, cultural escape, took place backwards in time: Chinese intellectuals affected a retreat into their glorious antiquity and undertook a systematic investigation of the splendors of their past. (Modern scholars have called this phenomenon “Chinese culturalism“ and see it, see in it a forerunner of the nationalism that was to develop many centuries later in reaction against the Manchu rule and Western aggressions).

In this perspective, antiquarianism appears essentially as a search for spiritual shelter and moral comfort.”

21st Century

The Late 20th C. modernisms were all over the place. Davidovsky, Carter, Wuorinen, Babbitt are utterly distinct. Minimalism is no less a modernism. Is the work of the minimalists any less distinct. I love Terry Riley for his stealth modernisms. I feel there is something there in common with Stravinsky’s neoclassical works – the stealth symmetries in the little cracks.

There’s at least this one case where the transatlantic cultural exchange strips away political elements. In Europe, Art Nouveau, Jugendstil and Liberty Style were reactions to the trappings of imperial architecture and the imperial-influence Beaux Arts.

American Art Nouveau is not. We understood the dynamic more than we felt them? They were abstractions to us? (Insert my Karl Krauss story.) Circumstances were different here.

Supranational

Polytonality

Ponce & Boulanger

The polytonal instrumental assignments in Sonata for Guitar and Harpsichord

“1918”

Bridge Burning

Schoenberg had to burn bridges. Americans understood the need more than they felt it.

On-shoring

Babbitt, August Stramm and John Hollander, Harold Bloom and the poets of our clime

Noise

Menachem Zur’s talk of Mario Davidovsky’s vision. See electronic music

Menachem Zur was positively inspired by a project that Davidovsky described to him, and yet Davidovsky abandoned the project. Lachenmann took it up.

Babbitt said famously, “nothing gets old faster than a new sound”. My position is less negative. New sounds do not necessarily ruin music. I am with Wolpe – “one has to earn the right to use silences”, he said to Meyer Kupferman. I assume Meyer’s pal Morton Feldman brought Meyer to a Wolpe gathering. I agree with Wolpe if he meant – silence can be a positive if one does not totalizing it as a value. The excitement about noise and microtones can make one forget our basic musical needs. Those needs do not have to be neglected by including noise, silence, microtones. Babbitt’s snark is aimed at the music that utterly abandons our core musical needs.

Some works of Lachenmann and Christopher Trapani suggest that we can do without some musical needs, just as Steve Reich’s Piano Phase taught us that we can yearn for the 16ths phasing into 32nds – supply-side musical economics. I never knew I would sit on the edge of my seat waiting for the phasing…..

I would nhot presume to define what musical needs are basic, but the extent to which certain needs are neglected, works that suddenly return to those needs, I’d expect to resonate strongly. But they might languish for a long time before getting a fair hearing. We are faddish.

Antinaturalism

Knut Hamsun’s telegraph operators were unhinged people. Crumb’s Black Angels, with its electric string quartet takes on the same unhinged quality. Frank Kermode talks at length about the dancer Louie Fuller and her dance, *Radium”. Interesting that she was American, but her success had to be in Paris.

Antipositivism

First suggested to me by David Claman’s *gone for foreign*. For the Bridge CD I discussed at length Claman’s positive joy in being is such a bizarre culture, where nothing quite translates.

Discussing Australian aborigines with a relative who had visited there, I was reprimanded for suggesting that there can be parallels between their archtypes and ours. This poses an interesting and unresolved question. I lean toward the position that we’re all humans and we all likely share some dream images. And the other contrary attitude is respectful of differences, puts weight on differences., enjoys differences, which is all good.

I thought I invented the term (antipositivism), but it’s been around for a century or so. Shortly after discussing Claman’s *gone for foreign* I encountered Baudelaire declairing that he despises anything “positif”. (In an introduction to Paris Spleen, I think.) Doesn’t this establishes a clear connection between antipositivism and antinaturalism?

Electronic Music

The vandalism of the Columbia-Princeton electronic music studio. I contend that the love and enthusiasm of flesh & blood players for the music of Brickle, Babbitt & Davidovsky drew those away from the electronic music studio. However, Babbitt told me that he never had the heart to go back to the Prentice Building after it was vandalized.

Electronic music will usually bring to mind antinaturalism. I don’t love Davidovsky’s electronic music, but his work in that medium made him who he was, shaped the sensibility of the creator of the Ladino Songs and Romancero.

Same with Babbitt his approach to dynamics comes from his long hours of tape-splicing and listening and noting how unfoldings can be sequestered by dynamic level, which he continued to do in music for traditional instruments.

Romanticism and anti-naturalism

Knut Hamsun’s telegraph operators & Crumb’s black Angels

Quidditas

I spoke of “whatitisity” and Brickle liked that, saying its a good translation of “quidditas”.

Taking or re-taking, or the twice-taken cannot happen without a taking. Something becomes a thing before it can be taken any which way. Often a composer builds up to a double-take, where an interesting counterpoint of values plays out.

Revise and rearrange:

Adjacencies

The Rockwell Coup expands our palette to include diatonic relationships that were once too tonal for the bridge-burners.

One way of looking at the octotonic scale is as a minor 7th chord transposed through the 3 cycle (transposed by minor thirds)

Diatonic minor 7th chords are a minor 7th chord transposed by 4ths – the iii7, vi7 and ii7. Those harmonies in that relationship were taboo for the bridge-burners.

Let’s say the functional minor 7ths are an extension of the octotonic minor 7ths and the octotonic minor 7th can be *extended* by dipping into the diatonic minor 7ths.

–Extended in what way?

–We preserve the *chord quality*.

We’d speak of *prolonging* a collection.

The augmented scale can be seen as major7 chords transposed by major thirds.

Augmented scale (aka “E hexachord”) major 7ths can be *extended* by a diatonic move. There are only two major 7th chords in the diatonic universe – Imaj7 and IVmaj7. But that relationship was mostly taboo before the Rockwell Coup.

William Anderson is a guitarist and composer and an advisor to the Roger Shapiro Fund.